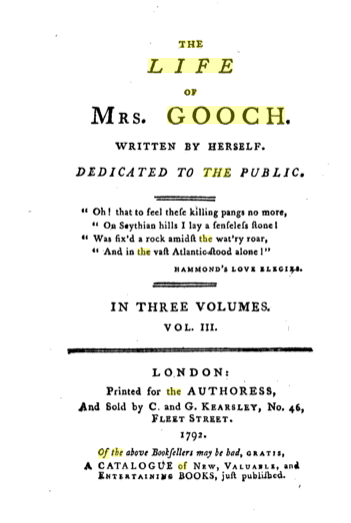

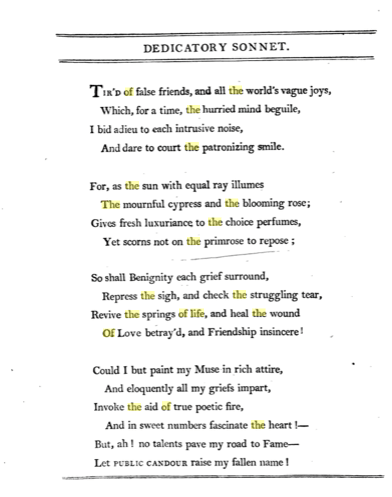

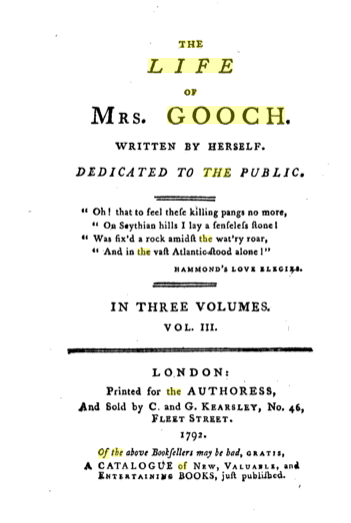

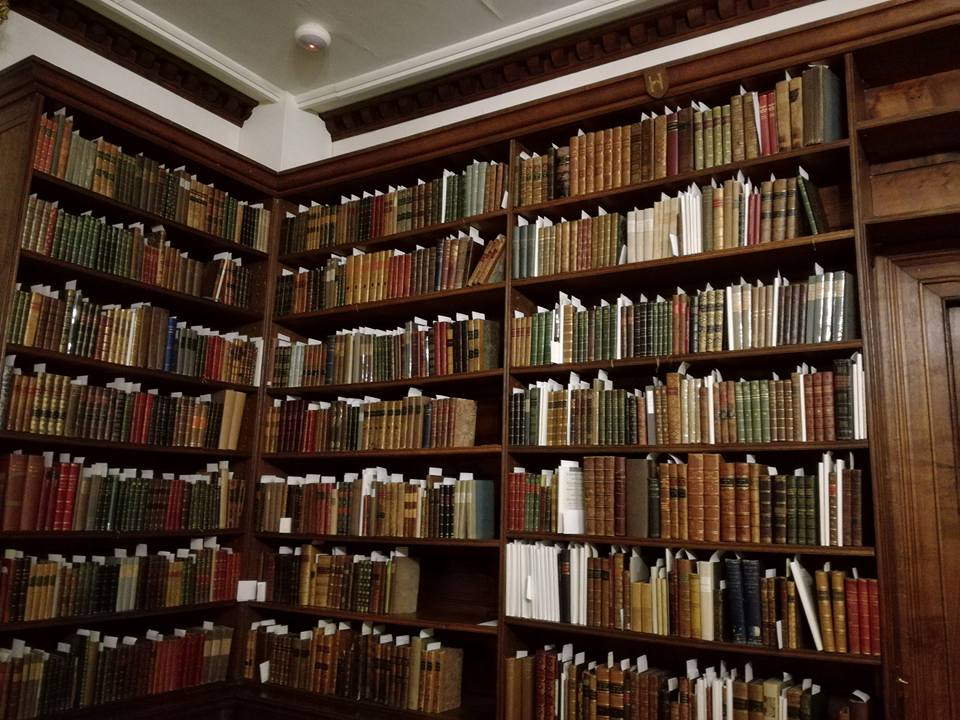

Today, I spent more time working in the fantastic library at Chawton and while I read many, many books trying to track down literary references to music lessons, I am most intrigued by a rather scandalous account retold by Elizabeth Sarah Villa-Real Gooch (1757-1807) in her memoirs The Life of Mrs Gooch. Perhaps Elizabeth felt that retelling the story in her owns words would somehow vindicate her name, demonstrating that she was not at all a ‘fallen woman’, but her account raises a few eyebrows.

Before getting into the ins and outs of the scandal, a little on Elizabeth. She was the daughter of a wealthy Portuguese Jewish merchant William Villa-Real, who was the grandson of Joseph da Costa (1683-1753). After being pursed by William Gooch, whose father was Sir Thomas Gooch of Bath, they were married in 1775 after only knowing each other for 4 weeks. Elizabeth was 17-years-old at the time.

Elizabeth describes William’s parents Sir Thomas and Lady Gooch as ‘never having taken a liking’ to her and she despised visiting them in Bath. In fact, she despised visiting Bath in general and far preferred her home in York. However, after the birth of her son in 1776, her husband decided to move the family permanently to Bath as of 1777. And from there our scandal begins…

Elizabeth notes that on a previous occasion she had sent for the castrato Venanzio Rauzzini (1746-1810) who had recently started to hold concerts in Bath. He was previously the lead singer of The King’s Theatre but had announced his return to the continent in the summer of 1777 with his final benefit concert being performed on the 4th July. Alas, Rauzzini never returned to the continent and remained in Britain until his death in 1810. Had he returned to Italy, the following episode would not have ensued and Elizabeth might have remained in her strange and somewhat unhappy marriage.

Elizabeth notes she had been ‘anxious to become a scholar of Rauzzini’s, who after being sent for, attended her each morning. She goes onto say that his public and private concerts were one of the only pleasures she partook in while in Bath.

So let’s set the scene a little more, graphically…

We have a desperately lonely woman, who despises the town she is forced to live in and her parents-in-law who are the reason she has been brought to said town. Her husband appears somewhat absent and one of her only joys is music. She has managed to secure for herself a music master who is a singer she deeply admires, and he comes to her home to give her lessons every morning. Now this may sound like a series of episodes leading up to a soap opera style drama, where Elizabeth was caught in the arms of her music master, spread in a precocious position on top of the harpsichord; however, the real scandal surrounds nothing more than a note.

Elizabeth claimed that Rauzzini handed her a note, written in French at a concert she was attending that stated:

‘Nothing more than an apology for his not being able to attend me the next morning, being obliged to go into the country; with an assurance, that he should return time enough for the concert, and stay the ball, on purpose to have the pleasure of seeing me.’ ‘

Yet, this note, which Elizabeth proceeded to misplace, resulted in her husband finding it and led to her public downfall and short expulsion from Britain. The note itself seems innocent in Elizabeth’s retelling, but she also states that Rauzzini had looked for it to be returned to him and once he found out it had been lost, led the castrato, his friend La Motte and another student and friend of Elizabeth, Louisa Kerr, to construct an elaborate lie where everyone agreed to say the note was written by another gentleman as a joke to Miss Kerr. Elizabeth protests that she was not comfortable with this construction, but proceeded to feed the lie to her husband anyway, which added fuel to the flames.

I reread this account several times, partly because it gives me so much information about the politics between a music master and his amateur students as well as practical arrangements, such as when lessons took place, how they were arranged and the benefits as well as downsides of having wealthy amateur students who clearly were in regularly attendance at subscription concerts (the 18th-century equivalent of subscription TV), but I also felt like I was missing something.

Why would Elizabeth go along with such an elaborate lie, if she is innocent? Why would she feel ‘fear’ that her husband would find out about the note. Certainly, one could construe Rauzzini’s reference, ‘the pleasure of seeing‘ you, as something more than collegial, but surely she would have done better to explain to her husband this was nothing more than a friendly statement? And then, why would Rauzzini refuse to have anything more to do with the situation if it were not more sordid? I suppose the answer to this final question is that the situation was already twisted into a sordid affair anyway, so he needed to keep clear to assert his innocents.

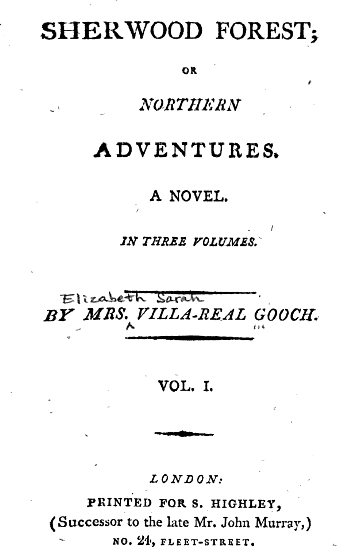

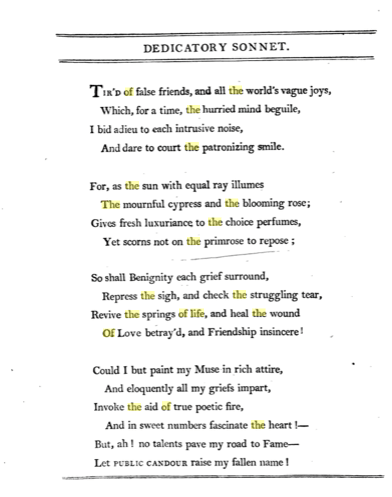

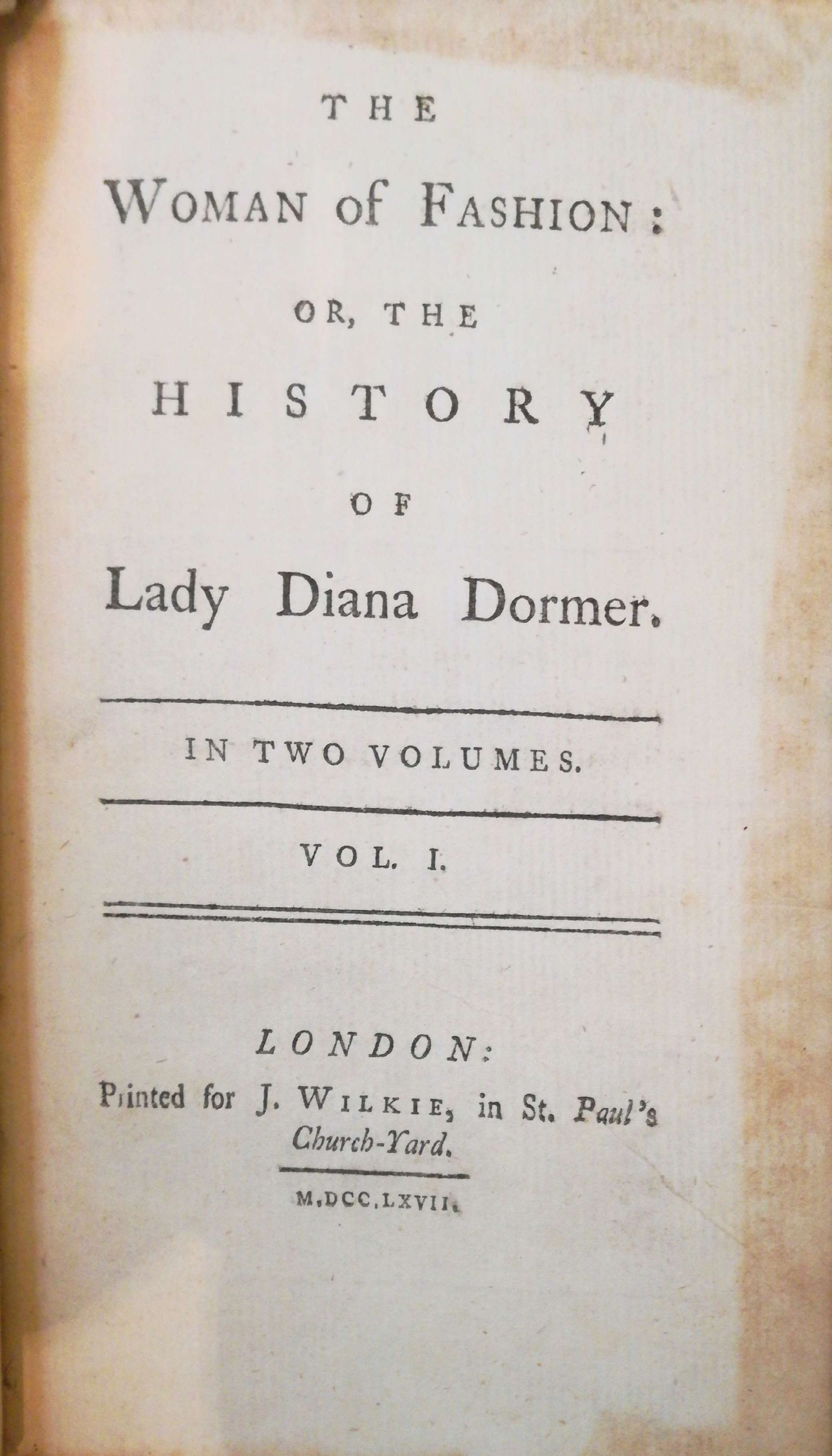

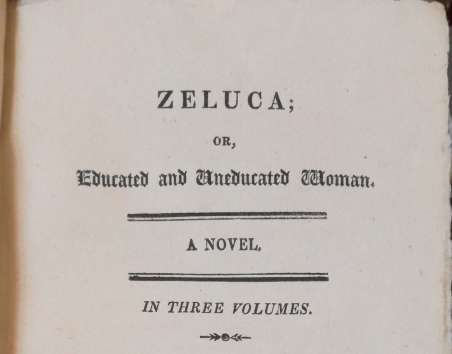

Alas, the mysterious note has long since disappeared into the vaults of unearthed history, but the scandal of Mrs Gooch, who maintained her innocents throughout her life remains. While her name was dragged through the mud and she was ‘reduced’ to becoming an amateur novelist (where she does discussed music frequently), Rauzzini’s career in Bath flourished. He built a healthy student base and ran the subscription concert series in Bath until his death. Unfortunately, in this scenario the reputation of the music master was saved, while his student was disgraced.

There are a number of literary accounts that paint a sordid image of the music master.

There are a number of literary accounts that paint a sordid image of the music master.

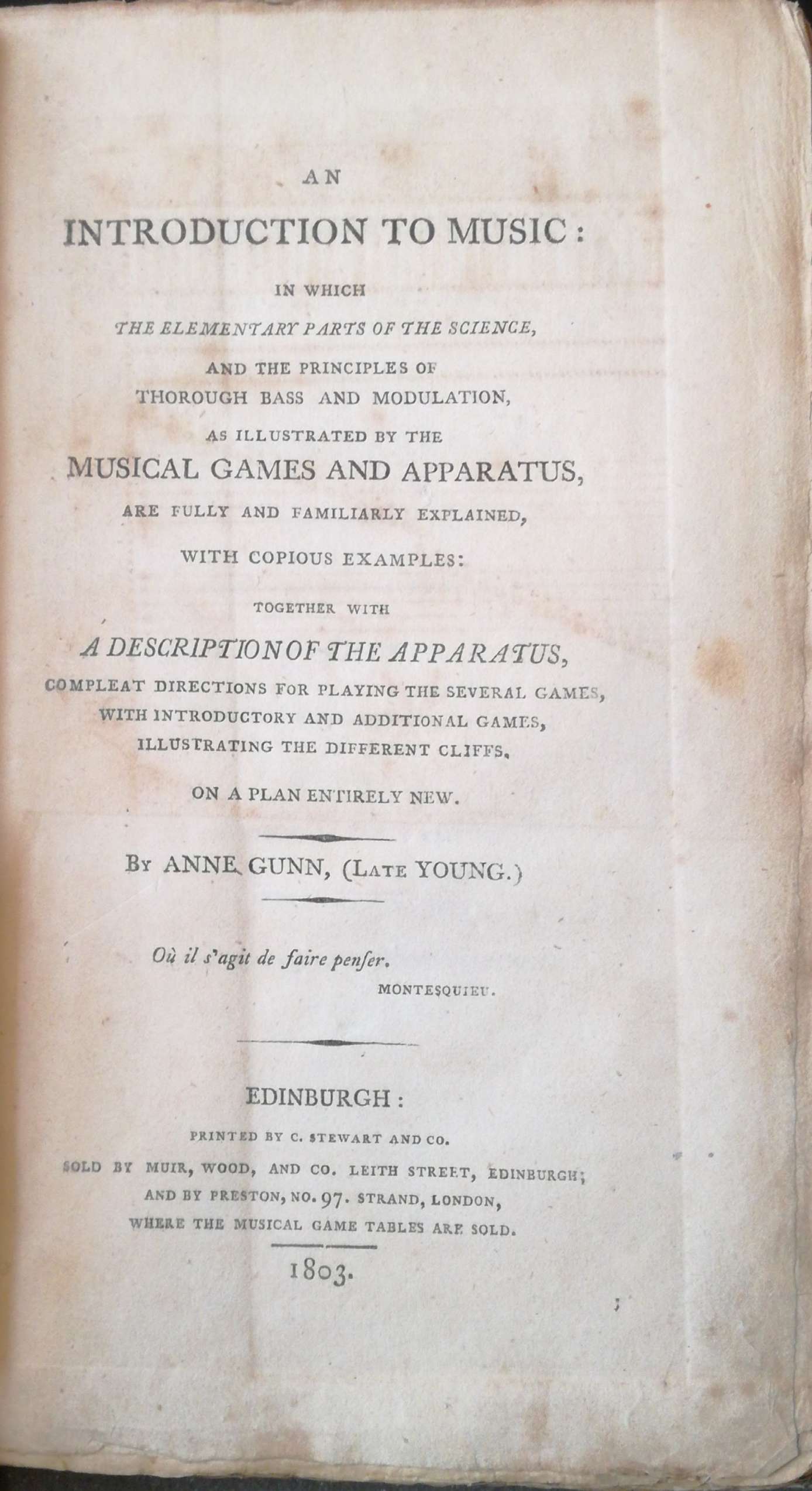

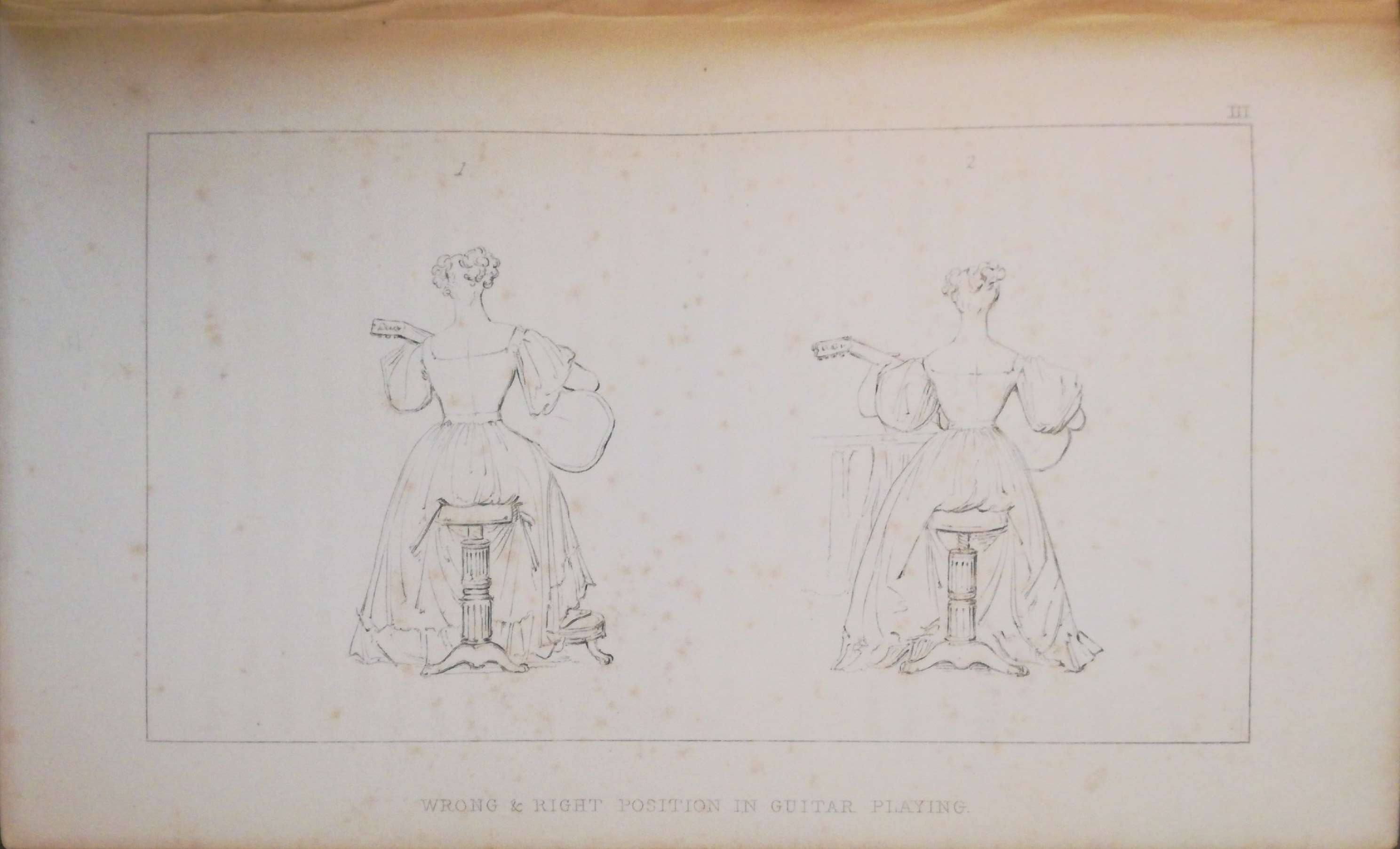

imparted all her knowledge. Morning lessons take place daily, which seems to have been the common time for music lessons during the period.

imparted all her knowledge. Morning lessons take place daily, which seems to have been the common time for music lessons during the period.